- Home

- Yuvi Zalkow

A Brilliant Novel in the Works

A Brilliant Novel in the Works Read online

A Brilliant Novel in the Works

a novel by Yuvi Zalkov

e-book ISBN: 978-1-84982-233-6

E-published in 2012 by

M P Publishing Limited

12 Strathallan Crescent

Douglas, Isle of Man

IM2 4NR, British Isles

M P Publishing Limited 6 Petaluma Boulevard North Suite B6

Petaluma, CA 94952. www.mppublishingusa.com

Zalkow, Yuvi.

A brilliant novel in the works / by Yuvi Zalkow.

5 “books,” 44 chapters

book ISBN 978-1-84982-165-0

1. Jews— Fiction. 2. Israel— Fiction. 3. Portland (Or.)— Fiction.

A CPI Catalogue for this title is available from the British Library This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

A Brilliant Novel in the Works

By Yuvi Zalkow

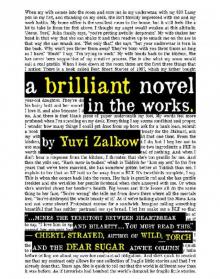

“Mines the territory between heartbreak and hilarity… You must read this.” — Cheryl Strayed, author of Wild, Torch, and Tiny Beautiful Things.

“If you buy just one book this year, consider resting this book on top of it. Yuvi Zalkow is a writer I’m going to watch from a safe distance.” — Gary Shteyngart, author of Super Sad True Love Story and Absurdistan.

for snuffalo

Acknowledgements.

This book was born at the Pinewood Table, where Stevan Allred and Joanna Rose lead one hell of a workshop. I learned so much from you two.

Cheryl Strayed. You helped me get this book out into the world. Thank you for your relentless support of me and my writing.

To my literary manager, Rayhané Sanders, for being a real champion of this book and my writing. And to my editor, Guy Intoci, for his faith in this book and for making it better.

Liz Prato, thank you for too many things, including our emergency check-ins. Jackie Shannon Hollis, our gossipy literary dinners. Laura Stanfill, Sarah Cypher, Shanna Germain in that Year of the Novel. Scott Sparling, your fabulous insane writing. Kate Gray, I knew you were incredible from that first workshop. Suzy Vitello, for great conversations and great advice and grappa. Christi Krug, your grace. Tammy Stoner, those great cocktails and conversations. Ellen Urbani, for truly bad ass feedback. To Tom Spanbauer, who has influenced many who have influenced me. Steve Taylor, I ache for our post-workshop wine sessions.

To my Antioch mentors: Leonard Chang, your pointed feedback was viciously valuable, and Alistair McCartney, you taught me a new way to see the particulars. Rob Roberge, who doesn’t realize I’m still angry I didn’t score mentorship time with him. Steve Heller, for allowing my ass into the MFA program.

Kate Maruyama, for all your kindness and damn fine insights. Jae Gordon, Stephanie Westphal, your support and love and more. Telaina Eriksen, for those fireside chats (I’m still resentful for the one that got interrupted). Stephanie Glazier, your great fabulosity and brilliant glow. Kristen Forbes, I miss our ‘writing’ sessions. To the fucking Sages.

Mom, Dad, hope my love shows even if I twisted many stories. Dan, I owe you for all the mileage your intestines gave me, and much more.

Sheri Blue. For a million things, on paper and especially not on paper. Dashiell, to you too. And of course to Savi, who does not yet realize how bald and worried his father really is.

Yuvi Zalkow is the creator of the “I’m a Failed Writer” online video series and has been rejected by reputable and disreputable journals alike. He has an MFA from Antioch and his stories have been featured in Glimmer Train, Narrative Magazine, The Los Angeles Review, Carve Magazine, and others. He lives in Portland, OR. Visit his website at yuvizalkow.com.

Contents

BOOK 1: GENESIS

CHAPTER 1: PANTSLESSNESS

ORIGIN OF SPECIES

CHAPTER 2: MASQUERADING

BLACKING OUT

CHAPTER 3: RIGHTEOUS ROOM

LOVERS AND THERAPISTS

CHAPTER 4: GETTING WET

I LOVE THE WAY YOU POOP WHEN YOU POOP WITH ME

CHAPTER 5: RESTRAINT

TALKING TO GOD

CHAPTER 6: NOAH

MATCHBOX CARS AND RAINBOW TROUT

CHAPTER 7: PALINDROME

BOOK 2: EXODUS

CHAPTER 8: A BRILLIANT NOVEL IN THE WORKS

SIGN LANGUAGES

CHAPTER 9: VERY NEARLY GOOD NEWS

SO YOU DON’T WANT TO BE A JEW

CHAPTER 10: HONEY MY ASS

CHAPTER 11: ALCOHOL AND STEROIDS

HOW I KILLED HER MOTHER

CHAPTER 12: THE WHOLE MEGILLAH

THE SMALLEST THINGS

CHAPTER 13: FAMILY

LAYING EGGS

CHAPTER 14: SHMUVI

THE GORILLA DID IT

CHAPTER 15: EVERYONE LOVES ME

BOOK 3: URANUS

MEN ARE FROM MARS, JULEFS ARE FROM URANUS

CHAPTER 16: LIFE WITHOUT HER

POTTY TALK

CHAPTER 17: BELLY OF THE HORSE

MEN ARE FROM MARS, JULEFS ARE FROM URANUS (CONCLUSION)

CHAPTER 18: PURPLE MONKEY DISHWASHER

MY AH-VAH-TEE-ACH FEVER

CHAPTER 19: SIMPLE SWOLLEN ANUS

THE POOP REPORT

CHAPTER 20: TELEPHONY

TENSE

CHAPTER 21: FUCK ME

RELATIONSHIP TROUBLE

CHAPTER 22: ISRAELIS ARE FROM ATLANTA, PALESTINIANS ARE FROM CLEVELAND, PART 1

ITALICIZED BACK STORY

CHAPTER 23: ISRAELIS ARE FROM ATLANTA, PALESTINIANS ARE FROM CLEVELAND, PART 2

CHAPTER 24: OFF THE TRACKS

SKETCH OF A PROSTATE

BOOK 4: MARS

CHAPTER 25: STALKING

CHAPTER 26: SLEEPER CELL

A FACE LIKE THAT (PART 1)

CHAPTER 27: A REAL MAN

A FACE LIKE THAT (PART 2)

CHAPTER 28: OFF WITH THE POTS

CONFESSIONS

CHAPTER 29: THIS IS NORMAL SEX

SHAME STORY #11 (TELL, DON’T SHOW)

CHAPTER 30: NOT THE WORST KIND OF NIGHTMARE

CHAPTER 31: HOME

BOOK 5: IN THE END

CHAPTER 32: YUMMY

THROAT CLEARING

CHAPTER 33: BAD DATES

WHAT TO DO WITH SHOSHANA?

CHAPTER 34: ETHNIC PLOT DEVICE

CHAPTER 35: PALOOKAVILLE PEE PEE PARTY

CHAPTER 36: TRAITORS

CHAPTER 37: END OF BUSINESS

CHAPTER 38: BROTHER, CAN YOU SPARE A PALINDROME?

CHAPTER 39: OUT TO DRY

MOUNT PISGAH

CHAPTER 40: FROM UP HIGH

CHAPTER 41: WHAT DO YOU SEE?

ODE TO FATHER

CHAPTER 42: PEEK SOUL

CHAPTER 43: SAVE ME, JULIA

CHAPTER 44: A BANISHED TYPO

Book 1

GENESIS

Chapter One

Pantslessness

When my wife comes into the room and sees me in my underwear, with my $30 Lamy pen in my fist, and standing on my desk, she isn’t terribly impressed with me and my work habits.

My home office is the smallest room in the h

ouse, but it still feels like a lot to take in from ten feet up. I thought my angst would weaken at this altitude.

“Jesus, Yuvi,” Julia finally says, “you’re getting awfully desperate.” My wife shakes her head in that way that she can shake it and then reaches up to smack me on the ass in that way she can smack it.

“Not only that,” she says, “but your underwear is torn in the back. Why won’t you throw them away? They’ve been with you three times as long as I have.”

“Hush!” I say. “I’m trying to work.”

My wife heads back to the kitchen.

She has never been supportive of my creative process. She is also what my mom would call a real gentile. When I look down at the room these are the first three things that I notice:

There is a book called Best Short Stories of 1997, which my father bought me at a used bookstore, on the floor beside my desk. He bought it as a gift for me upon announcing that he had prostate cancer. What kind of person gives an “I have cancer!” gift?

There is a photograph of my wife’s younger brother. The one with ulcerative colitis. The one we call Shmendrik. The one who reads faster and holds a job worse than anyone I know. It’s a picture of Shmendrik and his girlfriend’s eight-year-old daughter. They’re doing push-ups. Both their jeans are pulled down so that his hairy butt and her munchkin butt are showing. This photo is on my desk because I love it, and also because I don’t quite know what to do with it. He gave us two copies.

And there is that blank piece of paper underneath my feet.

My words feel more profound when I’m standing on my desk. Everything I say seems confident and proper. I wonder how many things I could get done from up here: ask for a bank loan, submit a book proposal, pray to my dead parents, write a peace treaty for the Middle East, ask my wife to take off her clothes and dance the way she did that one time.

From the kitchen, my wife asks me if I want a sandwich. I say that I do, but I beg her not to use mayonnaise or bacon.

My wife claims that without those two ingredients a BLT is worth nothing. I ask her if she’d use the word bupkis instead of nothing. And when I don’t hear a response from the kitchen, I threaten that she’s too gentile for me.

She yells out, “Kush meer in tuches,” which is Yiddish for “kiss my ass.” In the five years that we’ve been married, she has somehow gotten better at Yiddish than me.

I explain to her that an LT isn’t so far away from a BLT. It’s two-thirds complete, I say.

This is when she comes back into the room. Her hair is gentile red and she has gentile freckles and she wrinkles her gentile forehead when she’s annoyed with me. Or when she’s worried about her brother’s health. Big issues and little issues all do the same thing to her face.

“You’re wrong,” she tells me from down there where all the mortals live. “You’ve destroyed the whole beauty of it.”

As if we’re talking about the Mona Lisa and not some absurd Protestant excuse for a sandwich. Imagine calling something beautiful that has neither pastrami nor rye bread.

I let her make me a BLT so that she’ll leave me alone.

My wife wasn’t as excited as I was about these photographs of her brother’s ass. When she saw them, she closed her eyes and shook her head as if to say, “I love him in spite of this.” But I love him because of this.

I was the one who named her younger brother Shmendrik. Why else would a thirty-five-year-old man from Iowa have a name like that? In Yiddish, it means someone who is clueless. If I didn’t care for him so much I would have never given him that name.

I come down from the desk even though it means confronting that blank piece of paper.

My editor is quick to remind me that I owe her a novel. By quick, I mean that she doesn’t even say hello before telling me about my overdue contractual obligation. And she’s quick to remind me that my contract only allows for one collection of fragile little stories and that I’ve already done that. Years ago. She is quick to tell me that the world is different now than it was before. As if terrorists had bombed the world’s demand for fragile little stories.

Ever since I realized that I owe her a novel—a real novel, not a pretend novel, but a thing full of the meat and bones and feathers and foreskin that any good novel must possess—what I’m writing these days is bupkis.

I’ve decided that I’m willing to lose three fingers and six toes for something to appear on the page. I’d take four toes off one foot and two off the other. At least one foot would still have a majority of toes intact.

When I told my wife what my editor said, my wife made it sound simple. “So write a novel,” she said. And when I told her that I can’t write a novel, she said, “So to hell with your editor. Keep writing your fragile little stories and find another way to make money.”

She’s always trying to solve my problems. My people don’t tend to solve problems that easily. We don’t even want to solve problems that easily. My people suffer. We’re professional sufferers.

“Give it a rest with you and your people,” my wife keeps telling me. “You’re no more Jewish than Soon-Yi.”

#

I thank my wife for the BLT and close the door to my office. A minute later she slips a paper towel under the door and I notice that she sneakily wrote “Luv u” on it. Which is sweet— even with the incorrect spelling—except that it reminds me of the note I found in her pants pocket.

My wife’s L’s are so loopy that I tilt my head to see if it says something else in there.

I put the plate with the Protestant sandwich on my blank page. The bacon sticks arrogantly out of my sandwich. While my wife helps recovering alcoholics and listens to secrets that have been bottled up for twenty-seven years, I scratch my ass through torn underwear and whine.

I resent that my fragile stories no longer work. But I’m not sure whom to resent.

ORIGIN OF SPECIES

We buried my mother in a Jewish cemetery in Atlanta. As she was dying, she forgot how to speak English. It was Hebrew all the way down. She was from Israel. She met my father there, moved with him to Atlanta, and they raised me in the States. Matrilineally, my mother was the seventh generation born in Jerusalem. Her father lived and died in Jerusalem, but he was born in Iraq, in Basra, back when there was a Jewish community in that land.

I scattered my father’s ashes in the Davidson River, in the Pisgah National Forest, in North Carolina, where he was born. He lived in many places, including Atlanta and Israel. His parents were born in Poland. They escaped Hitler, passed through Ellis Island, and lived out their days in this North Carolina forest.

I was born in the Negev desert in Israel. I grew up in Atlanta. And now I live in Portland, Oregon, where Israel feels further away than Uranus. I like to tell people that I’m lost between worlds, but I don’t really know which worlds I’m between.

A year before he died, my father told me he wanted to be cremated. This isn’t something typically done by Jews, especially after the Holocaust, but it was what he wanted. These mountains feel like my home, he said to me. We were standing by his favorite river and we listened to the water for some time before he spoke again. Maybe we’re a lot like salmon, he said. At this point in his life, he was a fly fisherman more than anything else and he felt that everything could be better understood through fishing metaphors. I asked him what he meant about us being like salmon because I often didn’t get his metaphors. Just like salmon, he told me, we want to come back to where we started. We want to make a mark on this earth. And once we make some kind of mark, we’re ready to die.

Chapter Two

Masquerading

“Get your pants on,” Julia tells me. “We’re going out.”

“I don’t want to put my pants on,” I say. “Why don’t you take your pants off?”

She says, “If you want me to be pantsless at the Righteous Room in front of my brother and his girlfriend, then just say t he word.”

It’s a game of chicken and she knows I can’t win.

I already get jealous of the men who stare at her when we go out in public.

“Okay,” I say. “You win. Pants all around.”

She’s right that I need to put on my pants. She’s right that I’m not as Jewish as I advertise. My wife is right that my writing is getting too desperate these days. She’s right about a lot of things.

But I’ve got a pretty good list of things that she doesn’t know. She doesn’t know that I give her brother $300 a month for his debts. She doesn’t know that I found a note on a cocktail napkin in her pants pocket that said in a mess of a man’s handwriting, “Save me, Julia.” Scribbled by one of those men who can no longer distinguish between capital and lowercase, cursive and print, married and single. She doesn’t know that the dreams about my dad are getting so bad that I’ve been using her brother’s painkillers to get some sleep. My wife doesn’t know I’ve started making cuts on my ass with a razor blade (again) so that when I sit down, I feel the burn something awful. She doesn’t know I’ve quit going to my most recent therapist. She doesn’t know exactly how desperate I’ve become.

You should know: I’m not an asshole. I don’t want to keep these things from her. It’s just that one little thing became two little things, and then, five years later, we are living our lives within the secrets behind our lives. Even meaningless ones—I don’t tell my wife that I hide pictures of her as a child under the mattress. In one picture, she’s in pigtails and making a frowny face like someone stole her lollipop. I look at them every morning after she goes to work.

“You need to get out of the house more,” my wife keeps telling me. “It’s not good for you to be here all the time. Who knows what happens all those hours that I’m gone. Go to a café. Hang around other people. Maybe you’ll meet another writer who’s as scared to put on their pants as you are.”

“Maybe,” she continues, “if you got out of the house more, you’d stop brooding so much about your damn editor and get something done.”

A Brilliant Novel in the Works

A Brilliant Novel in the Works